Its fidgety freestyle finally broken down into breathy hyperventilations, she then unfurls her swathes of spectral adornment to wield bulb such as to cast imposing and utterly expressionless silhouettes on the silky drapes beyond, prior to singing to the singe of exposed filament on folksy number Le Berger. Its raw emotivity is illumined yet further by the sparse and shadowy visuals that here create an instantly unforgettable ambience: these blackened figures inhale menacingly as Camille approaches their human contemporaries, only to swiftly deflate and dwindle as she dawdles off somewhere else. Among its closing tones she then profits superbly from the proximity of mouth to "Madonna-mic": with honour and dignity restored to this piece of inherently '80s pop heritage, she imitates Andean pipe in demonstration of the great depths to her vocal range.

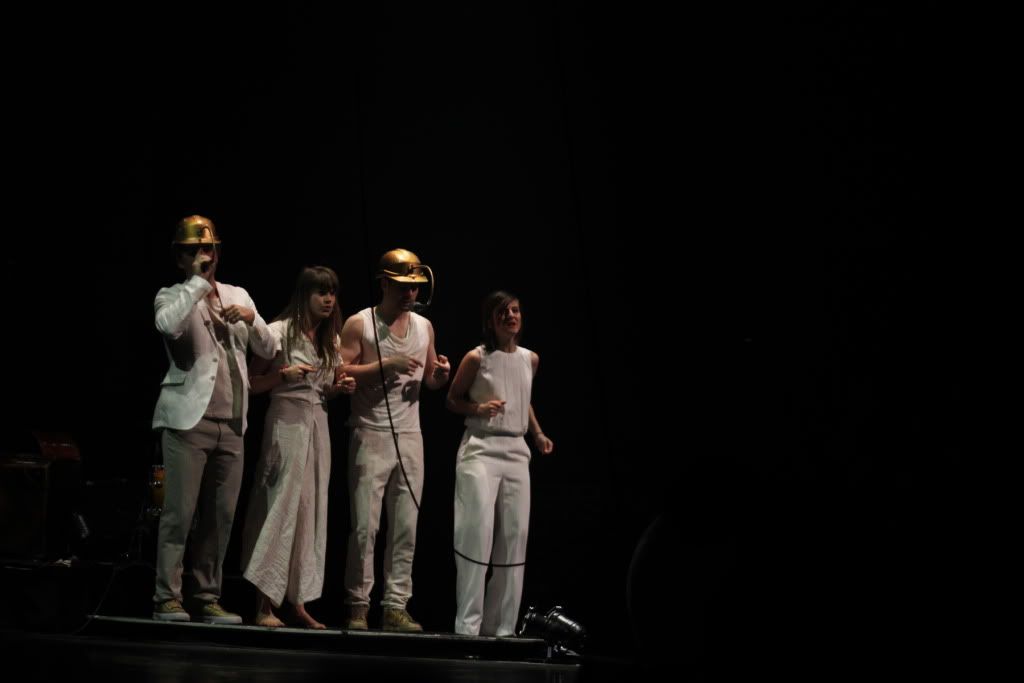

However whilst she may be the embodiment of an enviable, practically intangible purity then her rudimentary string section proves fundamental: backed only by an attritional three-piece band adorned in shiny, shiny hardhats opening moments intermittently pertain to the loose yet well-versed '60s lethargy of The Velvet Underground with a similarly effortless chic exuded. These frivolous gaieties are then wondrously offset by the gentle discomfort of the exotic unknown, for which the Gallic progressions of L'étourderie may here be explicated: Camille now becomes demented orchestrator, determining not only which band member may strut in and solo at which predetermined point with a wiggle of that bulb to dictate the size, shape and stature of each shadow in accordance to overall relevance to the overriding sound produced, but also furiously jiggling the thing to signal points of applause as though we were constituents of a ghostly TOTP production. The periodic, preordained entrances of her top-hatted henchman too add yet more kooky zaniness to this memorable soirée.

Yet whereas many artists vainly attempt to incorporate elements of the concertedly outré into their general (and oft generic) demeanour, Camille appears an authentic eccentric – she will later demand odd socks from bewildered audience bods in order that she may moonwalk midway through a protracted take on Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'. And this genuine oddness combines with the subjectively exotic on the title track as ordered in monkish garb, her unfathomably deep and otherwise delightfully light vocals take in every tonal deviation of an entire monastery. For if to brand Camille supernal in celestial sense may be somewhat hyperbolic then she's at least irrevocably external to the maddening hubbub of London. We can only wish you'd experienced Mars Is No Fun: like lost Joanna Newsom number floating through some unchartered niche of the universe, if her dangly locks attest to this parallel with everyone's preferred feline yelper then that she does the splits whilst yodelling of shopping malls in Milton Keynes (an Anglicism wonderfully juxtaposed with reintroduction of rhythm to "Un; deux; trois; quatre") sets her apart from anyone and indeed everyone. She tonight becomes the provider of a great jouissance that's practically nonpareil.

There's a jejune perfection to the bloopy choral babble of Bubble Lady as she swigs and gurgles water while bubbles are blown by a cross-legged, suddy-eyed pair stage-left. Its recorded madness finally imbued with great method that which follows, Shower, perpetuates the impression that Camille is of gradually diminishing age as she caterwauls as if sprawled out on bathroom floor: "I don't wanna get outta the shower, mama", her again feline hisses demonstrating a humanly perceptible reluctance to mature. Her lyrical exaggerations too are relatable to the recalcitrance of youth: "I don't wanna die" she bemoans and groans, now perhaps implicating hypothermia in place of earlier hyperventilations before hair-raising violins add theatrical impression to yet another childish interlude in the Frère Jacques-infused Message. It's as though she's the female counterpart to F. Scott Fitzgerald's fictitious convalescent Benjamin Button as she continues to seemingly grow ever younger – and with it her attention span shorter – with the passing of time during her all too brief London sojourn. However if her age – our at least our perception of – may fluctuate throughout, she may henceforth be perceived to be ageless and, in turn, tonight may truthfully be considered ultimately timeless.

And the moment that'll perhaps live longest in recollection is the indulgence in patriotic operatics aroused by La France: spouting gibberish, she proceeds to matchmake the utterly mortified; constructing a couple to left-footedly waltz and wince through the Ilo Veyou standout. The lights raised, a bemused bloke is hauled up. Invited to bury his head in her brassiere, he's then unwillingly cajoled into conversation on differing cup sizes. With his partner meticulously selected, if initially instructive Camille soon becomes that personally invasive, perennially unfulfilled ballet instructor. "No; no; no: comme ça!" she caws in what is perhaps the most bizarre moment of onstage theatricality witnessed thus far this year, and that despite Cate Blanchett interpreting Botho Strauss' Gross und Klein next door. She disparagingly whoops: "Mon dieu!" as we're helplessly plunged into hysterics; compulsively pushed to hypnotically clap along with gormless enthusiasm to vocals throaty enough to suggest Jacques Brel were here among us, mischievously sat atop contextually cited photocopier with his trousers down round his ankles.

There's a jejune perfection to the bloopy choral babble of Bubble Lady as she swigs and gurgles water while bubbles are blown by a cross-legged, suddy-eyed pair stage-left. Its recorded madness finally imbued with great method that which follows, Shower, perpetuates the impression that Camille is of gradually diminishing age as she caterwauls as if sprawled out on bathroom floor: "I don't wanna get outta the shower, mama", her again feline hisses demonstrating a humanly perceptible reluctance to mature. Her lyrical exaggerations too are relatable to the recalcitrance of youth: "I don't wanna die" she bemoans and groans, now perhaps implicating hypothermia in place of earlier hyperventilations before hair-raising violins add theatrical impression to yet another childish interlude in the Frère Jacques-infused Message. It's as though she's the female counterpart to F. Scott Fitzgerald's fictitious convalescent Benjamin Button as she continues to seemingly grow ever younger – and with it her attention span shorter – with the passing of time during her all too brief London sojourn. However if her age – our at least our perception of – may fluctuate throughout, she may henceforth be perceived to be ageless and, in turn, tonight may truthfully be considered ultimately timeless.

And the moment that'll perhaps live longest in recollection is the indulgence in patriotic operatics aroused by La France: spouting gibberish, she proceeds to matchmake the utterly mortified; constructing a couple to left-footedly waltz and wince through the Ilo Veyou standout. The lights raised, a bemused bloke is hauled up. Invited to bury his head in her brassiere, he's then unwillingly cajoled into conversation on differing cup sizes. With his partner meticulously selected, if initially instructive Camille soon becomes that personally invasive, perennially unfulfilled ballet instructor. "No; no; no: comme ça!" she caws in what is perhaps the most bizarre moment of onstage theatricality witnessed thus far this year, and that despite Cate Blanchett interpreting Botho Strauss' Gross und Klein next door. She disparagingly whoops: "Mon dieu!" as we're helplessly plunged into hysterics; compulsively pushed to hypnotically clap along with gormless enthusiasm to vocals throaty enough to suggest Jacques Brel were here among us, mischievously sat atop contextually cited photocopier with his trousers down round his ankles.

Allez Allez Allez retains such staunch nationalism, another a cappella powerhouse with the hardhats to prove it as these reported workmen stomp hard and fast down upon the sonorous slab of flooring where bubbles were only recently once blown whilst My Man Is Married But Not To Me exhumes that Feist parallel, only to pair its skeletal figure off with boisterous hip hop bound. Camille here comes across as prissy and above all particular, particularly petulant teen mistaking herself for distressed damsel long of lock and short of patience. She vainly awaits her so-called "hard lover" to arrive "on his horse; white horse", her quaint set then plunged into darkness for her naïve exploration of the dichotomy between pain and Pleasure that's sexually panted from the discomfort of stage floor. It's again overtly theatrical and, crumpled in post-coital position, it's as though knight in shining armour upon trusted steed had galloped up to sealed-with-a-slam bedroom door having heeded her screechy, adolescent yells. Another masterstroke in setlist composition, she turns siren-like on the segueing Wet Boy and, gilded with glistening silver screen qualities, its sexual connotations serve to smear another form of glisten over its seductive ways. Again setting and staging combine in consummate harmony: accompanied by a sole guitarist behind silky sheet, she's left to serenade this untouchable object of lust, only his shadow in any way tangible to her lovelorn figure. It's a startling moment of almost cinematic splendour and her voice proving shuddering as per, the atmosphere of a taught sexual tension is achieved. Indeed as the breathy choral beatboxing of closer Tout Dit disintegrates into silence, you feel almost as though she may well have exhaled her last.

Although having thus far drawn nigh on exclusively from her latest LP, her primary encore serves as something of a greater hits indulgence: Paris encompasses Inspector Gadget interlude and Tom Waits-y ashtray splutter as she ends the thing in a post-backward roll crumple, before she then has the entire Hall miaowing and woofing rabidly to Cats and hurtling through madcap phonetic French alphabet on Nanana as we flex the very greyest of matter. And all this despite her evident bourgeoise appeal, as all eyes remain transfixed on the petite figure in the third-hand wedding dress. For perhaps tonight's greatest joy derives from the crazed immaturity that she enslaves within the body of a thirty-four-year-old: it proves bloody infectious and above all invigorating for all involved.

Things go totally Nouvelle Vague in unprecedented second encore, which is uninspiringly kickstarted by a cover of her compatriots covering Dead Kennedys' Too Drunk To Fuck as she and band gather round gigantic lightbulb for campfire singsong aesthetic. However as a story of that now-infamous west London football race row peeks from dimly lit tote, if comparatively worse may occur out in the banlieues of her native Paris it serves as a grim reminder of imminent return to a reality that's grimmer still. As albeit only for a short while, all seemed well with the world.